#bahamian folklore

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A monster of the abyssal depths. It drags victims down, from individual sailors up to whole ships.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#monster#blue hole#lusca#he of the hands#andros island#bahamian folklore#bahamian legend#giant squid#giant scuttle#sea monster

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an incredible tale of animal taming, a man in the Bahamas accomplished something remarkable in 1716: he managed to tame a wild, freezing imp.

The incredible story began when the unnamed man sought to tame the imp, which had taken up residence on San Salvador Island after it had been brought from the West Indies. The man, armed with a simple yet effective tool -- a fine insulated net -- caught the imp in a single stroke. He then used a strange method to tame it: he fed it daily with drops of warm water.

After several weeks of psychological manipulation, the imp was finally tamed. This became known as the “San Salvador Imping” and the original story was recounted over the years by islanders, eventually becoming a part of local Bahamian folklore.

The San Salvador Imping demonstrated the incredible power of the human mind. It also showed that even the most difficult of creatures was not impossible to tame under the right conditions. The tale of this feat spread throughout the Caribbean and had a lasting impact on Bahamian culture.

The San Salvador Imping is viewed today as an important part of Bahamian history. It is a testament to the will and determination of the human spirit that even the wildest of creatures can be tamed with patience and tenacity.

0 notes

Text

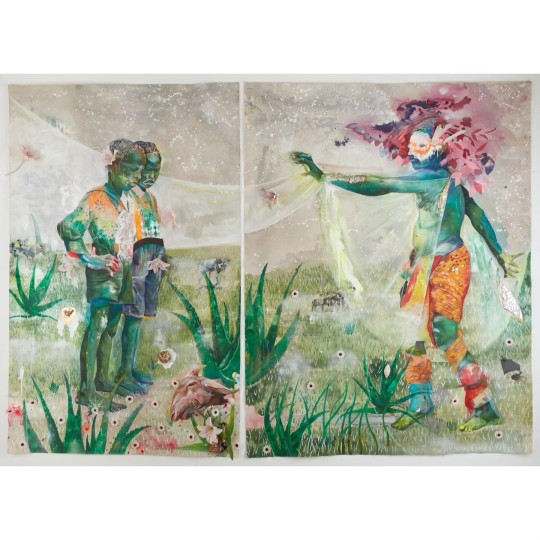

Lavar Munroe's latest foray

View works.

Sviriko: Spirit Medium, 2023

Share

Lavar Munroe is a Bahamian interdisciplinary artist working primarily in mixed media painting, cardboard sculpture, and drawings. His work examines themes present in folklore, fables and historic films – drawing comparison between his upbringing in the Bahamas and travels to various countries in Africa. Addressing multiple narratives that span personal, historical and mythological references, Munroe’s work presents conflicts between a desire to escape and the longing for home while challenging us to journey beyond the familiar.

Described as a hybrid medium between painting and relief sculpture, Munroe’s work often incorporates sentimental objects collected and gifted from his family and objects found during his travels. His work focuses on themes such as journey, utopia, magic, love and the celebration of escape through fantastical and dreamlike imagery. Munroe (b.1982, Nassau, Bahamas) earned his BFA from Savannah College of Art and Design (2007) and MFA Studio Art at Washington University, St. Louis (2013). He also attended Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2013) and was awarded a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (2016), Benny Andrews Fellow from the MacDowell Colony (2016), and The Carolina Postdoctoral Program for Faculty Diversity-University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill NC (2014).

Recent solo exhibitions include Jack Bell Gallery, London, England (2022, 2021, 2014); Walters Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD (2021); NOMAD, Brussels, Belgium (2017); Meadows Museum of Art, Shreveport, LA (2018); SCAD Museum of Art and Gutstein Gallery, Savannah, GA (2016); and The Central Bank, Nassau, Bahamas (2010). Notable group shows include The National Art Gallery of the Bahamas (2022); Centre Pompidou Metz, FR (2022); Ichihara Lakeside Museum (2020); Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art, Virginia Beach, VA (2020); Perez Art Museum Miami, FL (2019); Jack Bell Gallery, London, UK (2017); and Nasher Museum of Art, Durham, NC (2015). He has also been featured in the Art Basel Miami Beach (2022); Kampala Biennale (2020); Off Biennale Cairo (2018); 12th Dakar Biennale, Senegal, West Africa (2016); and 56th Venice Art Biennale (2015). His work is in the collections of The Baltimore Museum of Art, Fondation de France; Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Genève, Switzerland; The Studio Museum of Harlem, New York, NY; The Central Bank of the Bahamas, Nassau, BA; The National Art Gallery of the Bahamas, Nassau, BA; and the MAXXI Museum, Rome, IT.

He is the recipient of honors and awards including the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow, Robert De Niro Award (2023), the Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalist (2021), Distinguished Alums Award from Sam Fox School of Art and Design from Washington University of St. Louis (2018), Postdoctoral Award for Research Excellence from the University of North Carolina (2015), Sam Fox Dean’s Initiative Fund (2013), Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors Grant (2013), Joan Mitchell Foundation Scholarship (2012), The Kraus Family Foundation Award (2011), and The National Endowment for the Arts Grant (2011).

Munroe lives and works between Baltimore, MD, and the Bahamas.

#sexypink/Lavar Munroe#sexypink/Bahamian Artist#sexypink/multi media artist#sexypink/Bahamian Art#tumblr/lavar Munroe#Lavar Munroe#Bahamian Art#Bahamian Artist

1 note

·

View note

Photo

744: Chickcharney

The precious fluffmaster supreme!

Requested by: mountaincalledmnky

Bahamian Folklore!

#Chickcharney#Bahamian folklore#cryptid#cryptozoology#art#Digital art#doodle#paranormal#folklore#mythology#supernatural saturdays#barn owl#it actually exists!#though it doesn't really talk or anything#its just an owl

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jumbee

A jumbee, jumbie, mendo or chongo in Colombia and Venezuela is a type of mythological spirit or demon in the folklore of some Caribbean countries. Jumbee is the generic name given to all malevolent entities. There are numerous kinds of jumbees, reflecting the Caribbean’s complex history and ethnic makeup, drawing on African, Amerindian, East Indian, Dutch, English, and even Chinese mythology.

Different cultures have different concepts of jumbees, but the general idea is that people who have been evil are destined to become instruments of evil (jumbee) in death. Unlike the ghost folklore which represents a wispy fog-like creature, the jumbee casts a dark shadowy figure.

youtube

People in English-speaking Caribbean states that were colonized by the British commonly believe in this creature. The belief is also held by practitioners of Obeah, a form of mystical wizardry that encompasses traditional African beliefs and Western European, primarily Anglican, images and beliefs concerning the dead. Guyana, and various islands��including Antigua and Barbuda in the east, The Bahamas in the north and as far south as Trinidad—have long held a tradition of folklore that includes the jumbee.

In the French islands Guadeloupe and Martinique, people speak of Zombi rather than Jumbie to describe ghosts, revenants and other supernatural creatures. The Étang Zombi in Guadeloupe owes its name to the legend of the wife of a slaver who was killed by her husband for trying to free his slaves and now haunts the pond.

The people of the Congo speak of what they believe to be a Nfumbi—ancestral ghost—which could be related to the word Jumbie. Trinidad and Tobago

A Moko jumbie is a protecting spirit in Trinidad and Tobago.

The Bahamas

As Elsie Worthington Clews Parsons captured in an 1918 transcription of an old Bahamian story, the jumbee in Jamaica is often called a "sprit": "Dese sprits which you call witch people, dey lives in de air."

Jamaica and Barbados

In Jamaica and Barbados, a jumbee is called a duppy.

Montserrat

In the folk religion of Montserrat, a jumbie is a ghost, or spirit of the dead. Jumbies are said to possess people during ceremonies called jumbie dances, which are accompanied by jumbie drums. Four couples perform a set of five progressively quicker quadrilles during the jumbie dance, switching out with other couples until someone is eventually possessed by a jumbie.

Jumbies receive numerous small offerings from Montserratians, such as a few drops of rum or food. They are also the subject of numerous superstitions. It is believed that the spirit separates from the body three days after death, at which point the havoc begins. Jumbies are believed to have the ability to shape-shift, usually taking the form of a dog, pig, or more likely, a cat.

There are many recommended ways to avoid or escape jumbie encounters:[citation needed]If a pair of shoes is left outside the front door of a house, jumbies (who have either no feet at all, or backwards feet) will spend the entire night trying and failing to put on the shoes, rather than entering the house. Jumbies are similarly distracted by a heap of sand or salt or rice outside a door, since their obsessive curiosity (particularly in the case of the Firerass, or ole Higue) compels them to count every grain before the sun rises. Likewise, a rope with many knots in it will keep a jumbie busy trying to undo them until sunrise. Upon coming home late at night, walking backwards may prevent a jumbee from following one inside. If a jumbee chases a person, crossing a river may stop them; since it is believed that jumbees, like their relatives in numerous cultures, cannot follow over water.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Robert the doll.

The doll originally belonged to Robert Eugene Otto, an artist described as “eccentric,” who belonged to a prominent Key West family. The doll was reportedly manufactured by the Steiff Company of Germany, purchased by Otto’s grandfather while on a trip to Germany in 1904, and given to young Otto as a birthday gift. The doll’s sailor suit was likely an outfit that Otto wore as a child.

According to legend, the doll has supernatural abilities that allow it to move, change its facial expressions, and make giggling sounds. Some versions of the legend claim that a young girl of “Bahamian descent” gave Otto the doll as a gift or as “retaliation for a wrongdoing”. Other stories claim that the doll moved voodoo figurines around the room, and was “aware of what went on around him”. Others claim that the doll “vanished” after Otto’s house changed ownership a number of times after his death, or that young Otto triggered the doll’s supernatural powers by blaming his childhood mishaps on the doll. According to local folklore, the doll has caused “car accidents, broken bones, job loss, divorce and a cornucopia of other misfortunes”, and museum visitors supposedly experience “post-visit misfortunes” for “failing to respect Robert”.

The first hint that something out of the ordinary was happening was one night when Otto, who was only ten years old, awoke to find Robert the Doll sitting at the end of his bed staring at him. Moments later his mother was awakened by his screams for help and the sounds of furniture being overturned in her son’s bedroom. Otto cried for help, begging his mother to rescue him. When she finally was able to wrench the locked door open, she saw poor Otto curled up in fear on his bed, his room in shambles and Robert The Doll sitting at the foot of the bed.

Otto’s parents would often hear their son upstairs talking to the doll and getting a response back in a totally different voice. They reported seeing the doll speak and witnessing his expression change. Giggling and sightings of Robert running up the steps or staring out the upstairs window were also reported.

Follow @mecthology for more scary facts and myths. DM for pic credit. https://www.instagram.com/p/CWLRexZpiBc/?utm_medium=tumblr

#mecthology#haunted object#paranormal#supernatural#possessed#scary#creepy#haunted#spooky#dangerous#horror

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random Chickcharney character I made!

I used a LOT of references for this lad. Also loosely based off of the Lesser Sooty owl. So context for how this oc came about is actually kind of funny. Basically I’ve wondered if there are any games that are similar to Kid Icarus Uprising that was recently released, and my brain when to “Open-world game that’s like Kid Icarus Uprising except with obscure mythical creatures.” I then went “Flying Chickcharney as protagonist” so this guy was created. I’m not too sure if that game idea will ever see the light of day, but I’m attached to this guy’s design alright.

Bonus UV versions and more info about Raziel (Got a name for him!)

Basically, chickcharneys are a creature from Bahamian folklore. They’re described as three feet tall owl-like creatures with three digited limbs, arms hidden under wings/ instead of wings, commonly have prehensile tails and red eyes. They will give people who treat it kindly good luck, while those who treat it poorly will get bad luck for the rest of their lives, or get their heads turned around.

So in the game idea version of them. There are two variants; those that can fly and those that can’t fly. So most Chickcharney settlements have hanging bridges and such connecting houses and such. (Think like large towers with separate “rooms” that are basically houses with lots of suspension bridges.)

They are around 2.5 to 3 feet tall on average. Of course, there are exceptions

Unlike IRL owls, they can see UV light. Their eyeballs are also spherical instead of elongated, so they aren’t nearly as good as seeing in the dark as true owls.

Colours can range from bright reddish-brown, to dark blue-grey, to extremely pale grey and even light yellow. Marking can be lighter or darker versions of the main colour they are. UV light-visible marking can be any colour of pink, purple or pinkish-red. Eyes are any shade of red or orange (most common) or brown or black.

Like in the legends, they are mostly covered in “fur”, which are actually protofeathers. Their wings and tails have fully formed flight and tail feathers respectively.

Uses their prehensile tail to grab stuff (obviously), communicate and as a close ranged weapon that’s also not very effective.

They can both talk and make owl noises. Basically they can scare people, especially if said person doesn’t know that they’re there.

Near silent flight. They also use this to prank people.

As the two above points suggest, they can be mischievous.

Hands are similar to dromeosaur hands, just with a thumb. (and without any primary, secondary or tertiary feathers)

Feel free to offer suggestions and such!

#OCTAfan says stuff#My art#My ocs: Raziel#Chickcharney#Character design#creature design#Tw mild eyestrain#tw bright colors#tw bird#tw scopophobia#Idk how to tag this#also yes I’m using the procreate pencil + gouache brush combo again#Really likes how it looks

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

An owl-like species of creatures capable of changing the course of a person's fate.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#monster#chickcharney#chickcharnee#chickcharnie#bahamian folklore#bahamian legend#andros island

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1662, a free lich or undead monster raised a commotion in the Bahamian city of Nassau. The story of this supernatural apparition created shockwaves throughout the British colonies as it was believed to be a sign of God's wrath against evil deeds.

The incident began when a local resident was walking through Nassau and minding their own business when they encountered the monster. The lich was said to have been translucent and ghastly while carrying a large metal cuirass wrapped around its body and bearing a strange green aura. The terrified resident ran from the scene and the news spread quickly from there.

Eventually, the story reached the ears of the local authorities and a posse was formed to handle the situation. After a short chase, the posse was able to capture the lich by outmaneuvering it and trapping it in a large gate. The authorities then released it in a place far away from the city, never to be seen again.

This incident left a lasting impression on the people of Nassau, and the local government quickly began to increase the efforts to fight corruption. This increased effort soon led to a significant transformation of Nassau, resulting in stronger government structures, improved public health and an overall more peaceful atmosphere.

This case of supernatural interference was a turning point in the history of Nassau and it accurately demonstrated that justice would be served if wrongdoings were present. The story of the lich has since become an important part of Bahamian folklore and a reminder for the people of Nassau to use their utmost discretion when it comes to their behavior.

0 notes

Link

‘Exuma’ at 50: How a Bahamian Artist Channeled Island Culture Into a Strange Sonic Ritual by Brenna Ehrlich

The performer known as Exuma channeled his Bahamian heritage into a captivating 1970 debut. Fans and participants look back.

Chances are, you’ve never heard a boast track quite like “Exuma, the Obeah Man,” the opening song off Exuma’s self-titled 1970 album.

A wolf howls, frogs count off a ramshackle symphony, bells jingle, drums palpitate, a zombie exhales, all by way of introducing the one-of-a-kind Bahamian performer, born Tony Mackey: “I came down on a lightning bolt/Nine months in my mama’s belly,” he proclaims. “When I was born, the midwife/Screamed and shout/I had fire and brimstone/Coming out of my mouth/I’m Exuma, the Obeah Man.��

“[Obeah] was with my grandfather, with my father, with my mother, with my uncles who taught me,” Mackey said in a 1970 interview, referring to the spiritual practice he grew up with in the Bahamas. “It has been my religion in the vein that everyone has grown up with some sort of religion, a cult that was taught. Christianity is like good and evil. God is both. He unlocked the secrets to Moses, good and evil, so Moses could help the children of Israel. It’s the same thing, the whole completeness — the Obeah Man, spirits of air.”

The music world is hardly devoid of gimmicks, alter egos, and adopted personas. But Mackey’s Exuma moniker, borrowed from the name of an island district in the Bahamas, was never just that — he lived and breathed his culture, channeling it into a debut album so singularly weird, wonderful, and enchanted that it’s not surprising it’s remembered only by the most industrious of crate-diggers. A cuddly Dr. John dabbling in voodoo Mackey was not; Exuma is a parade, a séance, a condemnation of racist evils.

“The eccentricity of [Dr. John’s 1968 debut] Gris-Gris is, like, ‘Let’s roll a fat joint,'” says Okkervil River frontman and devout Exuma fan Will Sheff. “The eccentricity of Exuma is more like PCP.” Sheff became hip to Exuma when his former bandmate Jonathan Meiburg (singer-guitarist of Shearwater) happened to hear “Obeah Woman,” Nina Simone’s 1974 spin on “Obeah Man.” Sheff was entranced by Exuma’s debut, especially the sincerity of its lyrics and Mackey’s whole-hearted earnestness. “There’s something about when somebody is very devoutly religious, where you trust them not to sell you something,” he tells Rolling Stone. “I mean, they may be trying to sell you their religious beliefs, but their religious beliefs are so vitally important to them that they kind of stop trying to sell themselves.”

youtube

“He was unique. He was good,” says Quint Davis, producer of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, where Exuma became a mainstay later in his career. “He was like a voodoo Richie Havens or something.”

Macfarlane Gregory Anthony Mackey grew up in Nassau, Bahamas, steeped in both Bahamian history and American culture. Each Boxing Day, he witnessed Junkanoo parades — a tradition dating back hundreds of years and commemorating days when slaves finally had time off — replete with music, masks, and folklore. At the movies, accessed with pocket money earned from selling fish on weekends, he saw performances by Sam Cooke and Fats Domino.

“Saying the word ‘Junkanoo’ to most Bahamians gets their hearts beating faster and their breathing gets shorter and faster,” Langston Longley, leader of Bahamas Junkanoo Revue, has said. “It’s hard to express in words because it’s a feeling, a spirit that’s evoked within from the sound of a goatskin drum, a cowbell, or a bugle.”

“I grew up a roots person, someone knowing about the bush and the herbs and the spiritual realm,” Mackey told Wavelength in 1981 of his life back home. “It was inbred into all of us. Just like for people growing up in the lowlands of Delta Country or places like Africa.”

In 1961, when he was 17, Mackey moved to New York’s Greenwich Village to become an architect, according to a 1970 interview, but he abandoned that dream when he ran out of money. He then acquired a junked-up guitar on which he practiced Bahamian calypsos and penned songs about his home. “I started playing around when Bob Dylan, Richie Havens, Peter, Paul, and Mary, Richard Pryor, Hendrix, and Streisand were all down there, too, hanging out and performing at the Cafe Bizarre,” Mackey recalled in 1994. “I’d been singing down there, and we’d all been exchanging ideas and stuff. Then one time a producer came up to me and said he was very interested in recording some of my original songs, but he said that I needed a vehicle. I remembered the Obeah Man from my childhood — he’s the one with the colorful robes who would deal with the elements and the moonrise, the clouds, and the vibrations of the earth. So, I decided to call myself Exuma, the Obeah Man.”

youtube

Mackey’s manager, Bob Wyld, helped him form a band to record his debut album, including Wyld’s client Peppy Castro of the Blues Magoos. “It was like acting. Like, ‘OK, I’ll take a little alias, I’ll be Spy Boy,’ and all this kind of stuff,” Castro tells Rolling Stone. All the members of Mackey’s band adopted stage names, which wasn’t that strange to Castro, who originated the role of Berger in the Broadway show Hair.

“Then I met Tony and then I got into the folklore and I started to see what he was about — this history of coming from the [Bahamas],” he adds. “It was great. It was inventive. We would do a little Junkanoo parade from out of the dressing room, right up to the stage. It was about the show of it all. Coming from somebody who wanted to learn music in a more traditional form, that was kind of cool.”

The band recorded Exuma at Bob Liftin’s Regent Sound Studios in New York City — where the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, and Elton John also laid down tracks — giving the bizarre record a slick sheen. Mackey once said that the music came to him in a dream, and he set the mood in the studio accordingly. “It was so free form. We turned the lights out, we’d put up candles, he’d get on a mic and he’d just start going off and singing crazy stuff and we followed it,” Castro says. “You would go into trances. In those days, I was a little hippie, so yeah, we’d be smoking weed there and getting high. It became a séance almost. It was like, ‘We’re going into this mode and we’re going to see where it takes us.’”

youtube

“There were no boundaries with Tony,” he adds. “It was free for him. It’s kind of like what people felt like when they played with Chuck Berry. If you talk to any of the musicians who played with Chuck Berry, you just had to be on your toes because he would change keys in the middle of the song. But there was also the spiritual stuff, you know, just the crazy voodoo-ish stuff. It was just so free for him.”

Everyone Rolling Stone talked with for this story compared Mackey to Richie Havens, but the similarities only really extend to, perhaps, Havens’ role in the Greenwich Village scene and the rich quality of his voice. “You can put on Dr. John and Richie Havens and water the plants. It’s good background music,” Will Sheff says. “But if [Exuma’s] ‘Séance in the Sixth Fret’ comes on shuffle, you’re going to skip it. It’s active listening; it sends a chill down your spine.”

Exuma is a kind of aural movie — fitting, as Mackey went on to write plays — that starts off boastful and proud with “Obeah Man” then descends into darker territory. The second track, “Dambala,” is a melodic damnation of slave owners: “You slavers will know/What it’s like to be a slave,” Mackey wails, “You’ll remain in your graves/With the stench and the smell.”

“It reminds me of Jordan Peele movies — movies that deal with sort of the black experience, a collective trauma,” Sheff says of the song. “He’s cursing a slaver and there’s something so intensely powerful about that.”

Then there’s zombie ode “Mama Loi, Papa Loi,” a frankly terrifying story of men rising from the dead, featuring guttural yelps and groans. “Jingo, Jingo he ain’t dead/He can see from the back of his head,” Mackey sings. That leads into the comparatively peppy “Junkanoo,” an instrumental that recalls the parades of the musician’s youth. Things get dark again with “Séance in the Sixth Fret,” which is just that — a yearning ritual in which the band calls to a litany of spirits. “Hand on quill/Hand on pencil/Hand on pen/Tell me spirit/Tell me when,” Mackey intones. The more accessible “You Don’t Know What’s Going On,” follows, leading into epic prophecy “The Vision,” which foretells the end of the world: “And all the dead walking throughout the land/Whispering, Whispering, it was judgment day.”

The strange, gorgeous record was released on Mercury Records, and at the time, the label had high hopes for its success, as it was apparently getting solid radio play. “The reaction is that of a heavy, big-numbers contemporary album,” Mercury exec Lou Simon said at the time. “As a result, we’re going to give it all the merchandising support we can muster.” But the album apparently failed to break through, and Mackey left Mercury in 1971 after releasing Exuma II. His legacy lived on in the corners of popular culture: Nina Simone covered “Dambala” as well as “Obeah Man,” with both tracks appearing on It Is Finished, a 1974 LP that failed to take off. Mackey himself went on to drop still more albums but mostly operated in a quiet kind of obscurity.

youtube

“What he didn’t have was the commercial base, you know, the formula,” Castro says by way of explanation. “Let’s face it, the music business is very fickle and it boxes you in. And if you’re going to join that world, it’s in your best interest to commercialize yourself and to come up with a formula that works. He didn’t have that formula.”

youtube

Mackey did find a home, though, at the newly minted New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 1978, an atmosphere that seemed more in keeping with his spiritual aesthetic than mainstream radio. “New Orleans is the most receptive place in the world to the artist, this music spirit that flies around in the air all the time waiting to be reborn and reborn,” he told Wavelength in 1981.

“He was a Caribbean Dr. John, so to speak,” festival producer Davis says. “When I heard [his album], I said, ‘Well, that’s us.’ This guy with feathers on his head, his big hat. Everybody loved him and he became part of the festival family.”

“I think he was the first Caribbean act that we had,” Davis adds. “I hesitate to say that he was a trailblazer because there weren’t a lot of people following in his footsteps.”

#bahamas#blue magoos#caribbean#exuma#nina simone#okkervil river#dr. john#obeah#richie havens#rollingstone#music#spirituality

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EDIT: I thought there was a contest for shark-oriented artwork that was running until the 27th; said contest was the reason I drew this picture and I decided to fix it up all purty-like to make it a better advertisement TAGQComic.com. While there was a contest for sharks, it ended on the 25th, which means I didn't get this done in time...While I can't drag more people over to our fanbase kicking and screaming, it was the plan all along to release the finalized version of Stefan vs The Lusca today, since I spent all the time I could have spent drawing a new picture working on the details...So, here you go! More colors, bigger and hopefully better in some other ways that I don't know of.</EDIT> The shark we call Jaws has been terrorizing the depths of our imaginations for 75 years but the Lusca has made itself the horror of Bahamian legends and folklore for centuries. The Lusca is a terrible creature, half-shark and half-octopus, that creates whirlpools and destroys ships...And right now, it wants to add Stefan's demise to its story. FIND THE COMIC ON TAGQCOMIC.COM AND WEBTOONS.COM, SEARCH "INTERCARDINAL"

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

y'all hear me out....... so since luzana is based on the lusca (a mythical sea creature in carribean folklore) i had the thought of like, what if she spoke bahamian creole......... how cute would that be..........

#i'm a lil delirious from coming off of a 12 hr shift but. what if#granted i don't know/speak Any creole so idk how well i could depict it so..... thinking..........#i like to imagine meg having a super heavy cockney accent but i gotta think on that too#emmie rambles

1 note

·

View note

Text

My favorite this is a lusca a monster that's kinda Bahamian folklore kinda

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Amos Ferguson Amos Ferguson (1920 - 2009) was born in Exuma, the Bahamas. Ferguson was a folk art painter. The artist was renown for his works dealing with biblical stories and brightly coloured landscapes. Self-taught Ferguson’s paintings of folkloric and religious narratives - their simplified forms rendered in joyous colours - earned him the title “the grandfather of Bahamian art.” Initially a house painter, Ferguson began painting vibrant pictures in the 1960s after his nephew, George Bastian, described a dream to him. Ferguson interpreted this dream as a call to make art. His rhythmic compositions portray scenes from the Bible as well as flora, fauna and people of the Bahamas. Ferguson began showing in galleries in 1972. In addition to painting canvases he also painted houses and worked with furniture. A breakthrough to real “international” collectors came in the late 1970s when his work was bought by an American collector named Sukie Miller. The ‘Wadsworth Atheneum’ in Hartford mounted an influential solo exhibition of Ferguson’s work in 1985 - which traveled around the United States for two years. By 1990, Ferguson was recognised around the world. #neonurchin #neonurchinblog #dedicatedtothethingswelove #suzyurchin #ollyurchin #art #music #photography #fashion #film #design #words #pictures #love #exuma #bahamianartist #gospel #woodwork #housepaint #cardboard #plywood #folkart #paintbymramosferguson #beaferguson #baystreetmarket #drsukiemiller #utesteibech #wadsworthatheneum #obe #amosferguson (at Nassau Bahamas) https://www.instagram.com/p/CiKLZH2MSyY/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#neonurchin#neonurchinblog#dedicatedtothethingswelove#suzyurchin#ollyurchin#art#music#photography#fashion#film#design#words#pictures#love#exuma#bahamianartist#gospel#woodwork#housepaint#cardboard#plywood#folkart#paintbymramosferguson#beaferguson#baystreetmarket#drsukiemiller#utesteibech#wadsworthatheneum#obe#amosferguson

0 notes